[Source: cognitiontoday.com]

American psychologist Abraham Maslow once said, “I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.” In other words, we tend to rely on the same knowledge, perspective or “tool sets” to often propose the same familiar solution to every new problem that we encounter.

In a business context, a Maslow’s hammer of metrics often exists. We try to reduce all information to metrics that we can understand through our own history and perspective to transform the direction, focus and fortunes of a product. As someone working on a subscription / SaaS product myself, we rely on several metrics to analyze the customer lifecycle from end to end over a period of months, implement product and business model changes and measure the impact of these changes across a set of customer cohorts. However, an unwavering focus on optimizing these metrics can sometimes come at the expense of customers and the reality of the product. If we really want to understand customers, we need to accept that people are not fully predictable and quantifiable and bring nuance to how we use metrics to shape the product we deliver to them:

Find more real nails - i.e., measure what needs to be measured.

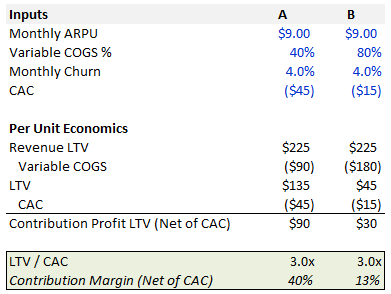

A key metric in growth strategy is the LTV/CAC ratio. At the highest level, LTV/CAC is the ratio of the estimated lifetime value (LTV) of a customer to the cost of persuading them to sign up (i.e., the customer acquisition cost/ the CAC).

Lifetime customer value (LTV) is calculated as a function of the following inputs:

Take the average revenue of a user in the quarter

Multiply it by the gross margin (to figure out how profitable a subscriber is), then

Divide this figure by the churn rate — the proportion of customers which leave each quarter.

Customer acquisition cost (CAC) is calculated by dividing the marketing costs by the number of paid subscribers added.

As a rule of thumb, a ratio of 3 or higher is indicative of a healthy business. However, as the data below suggests, two products both with a 3x LTV/CAC ratio, can tell a vastly different story.

Company A’s cushion from higher profitability suggests more room for the product to invest in further growth - through increased marketing and/or R&D, or expanding to new customer bases. Company B, on the other hand, likely needs to evaluate how to improve its margin health - either through increasing prices, reducing costs or a combination of both. In this case, exuberance about the ‘healthy’ LTV/CAC metric would reveal little about the underlying financial health of both businesses without also considering their contribution margins.

Use the hammer better - i.e., interpret what you measure correctly.

Metrics measure, but they don’t necessarily tell much of anything and in the worst case scenario, can be downright misleading.

Continuing with the LTV/CAC ratio example, product teams typically track the average LTV/CAC ratio as a key metric. However, if the goal of tracking this metric were to determine how much to spend in customer acquisition, anticipate future cash flows, or discover which factors drive your highest value customers, tracking only the average LTV would fail to provide any insight into what motivates a product’s top customers to spend as much as they do.

An organic customer who “chooses” your product will likely be more satisfied than one who is persuaded to buy your product through marketing spend. Given the varying customer dynamics, it is important to dig deeper into the metric in order to draw real real insight. For example, in this case, it is important to think through:

Whether newly acquired customers are more likely to make a repeat purchase, or less likely to make a repeat purchase, than organic customers in the past?

Whether new customers are spending more or less per transaction than older customers?

Whether your product marketing is improving or getting worse over time?

In this case, the more we can segment our customers before calculating and tracking LTV, the more actionable our insight from the metric becomes.

Consider using a screwdriver - i.e., realize that there’s sometimes insight to be uncovered beyond purely the metrics.

While "we optimize for what we measure”, it remains as important to identify unforeseen product outcomes to create value.

Proactively looking for qualitative, unstructured feedback on the products we develop to better understand how to meet customer needs can help realize a product’s full potential. For example, uncovering unexpected privacy, sustainability, or inclusion issues might not map neatly onto a tracked metric for a product but can affect a product’s growth trajectory by understanding that something happened and trying to fix it proactively, instead of trying to explain why something happened post facto in a monthly or quarterly sync.

(Hustle Fuel represents my own personal views. I am speaking for myself and not on behalf of my employer, Microsoft Corporation.)

Truly insightful. While there’s a rush to measure, one may lose sight of the range of outcomes and the context of such measurement